London, 5 May 1875

Dear Bracke,

When you have read the following critical marginal notes on the Unity Programme, would you be so good as to send them on to Geib and Auer, Bebel and Liebknecht for examination. I am exceedingly busy and have to overstep by far the limit of work allowed me by the doctors. Hence it was anything but a “pleasure” to write such a lengthy screed. It was, however, necessary so that the steps to be taken by me later on would not be misinterpreted by our friends in the Party for whom this communication is intended.

After the Unity Congress has been held, Engels and I will publish a short statement to the effect that our position is altogether remote from the said programme of principle and that we have nothing to do with it.

This is indispensable because the opinion – the entirely erroneous opinion – is held abroad and assiduously nurtured by enemies of the Party that we secretly guide from here the movement of the so-called Eisenach Party. In a Russian book [Statism and Anarchy] that has recently appeared, Bakunin still makes me responsible, for example, not only for all the programmes, etc., of that party but even for every step taken by Liebknecht from the day of his cooperation with the People’s Party.

Apart from this, it is my duty not to give recognition, even by diplomatic silence, to what in my opinion is a thoroughly objectionable programme that demoralises the Party.

Every step of real movement is more important than a dozen programmes. If, therefore, it was not possible – and the conditions of the item did not permit it – to go beyond the Eisenach programme, one should simply have concluded an agreement for action against the common enemy. But by drawing up a programme of principles (instead of postponing this until it has been prepared for by a considerable period of common activity) one sets up before the whole world landmarks by which it measures the level of the Party movement.

The Lassallean leaders came because circumstances forced them to. If they had been told in advance that there would be haggling about principles, they would have had to be content with a programme of action or a plan of organisation for common action. Instead of this, one permits them to arrive armed with mandates, recognises these mandates on one’s part as binding, and thus surrenders unconditionally to those who are themselves in need of help. To crown the whole business, they are holding a congress before the Congress of Compromise, while one’s own party is holding its congress post festum. One had obviously had a desire to stifle all criticism and to give one’s own party no opportunity for reflection. One knows that the mere fact of unification is satisfying to the workers, but it is a mistake to believe that this momentary success is not bought too dearly.

For the rest, the programme is no good, even apart from its sanctification of the Lassallean articles of faith.

I shall be sending you in the near future the last parts of the French edition of Capital. The printing was held up for a considerable time by a ban of the French Government. The thing will be ready this week or the beginning of next week. Have you received the previous six parts? Please let me have the address of Bernhard Becker, to whom I must also send the final parts.

The bookshop of the Volksstaat has peculiar ways of doing things. Up to this moment, for example, I have not been sent a single copy of the Cologne Communist Trial.

With best regards,

Yours,

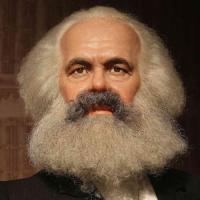

Karl Marx